BY AMY H. JOHNSON START PROGRAM EDITOR

The

Soviet Union's

One-Man

Game Industry

Alexey Pazhitnov didn't plan to be a global wunderkind, but the runaway success of Tetris made his name famous within the computer entertainment industry. When a star lives halfway around the word, however, few people get a chance to learn much about him. START caught up with Comrade Alexey on his whirlwind tour of the United States and peeked at the man behind the mega hit.

Alexey Pazhitnov doesn't want to face two more journalists quizzing him about sales, software and the Soviet Union. But publicity is a skill all successful entrepreneurs need to master and he approaches his task with grace and good humor, a little stunned to find himself a hot story in America. After all, he only invented a little game of falling blocks, a little game called Tetris, a little game that has sold millions of copies worldwide and made the modest Soviet mathematician a Western symbol of the emerging, glasnost-era capitalist.

Dressed in jeans and a grey sweater, the bearded, 34-year-old father of two looks more like the academic he is than the vanguard of a shifting economy. But ever since he arrived in America, landing in the middle of the swarming sales pitch that is the Las Vegas Consumer Electronics Show, he's been riding a public-relations blitz like a Cossack on a calvary charge.

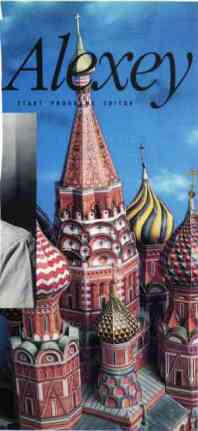

In San Francisco he attended a press reception in his honor at a plush hostess suite at Union Square's St. Francis Hotel. Local press and Soviet diplomats nibbled quiche squares and mingled with executives from Spectrum Holohyte, Pazhitnov's American publisher, who had obligingly installed computers loaded with his latest creation, Welltris, a 3D version of Tetris. (Spectrum estimates that the ST version of Welltris will be released around Christmas). The author patiently posed for pictures, answered questions and autographed game boxes. "Play TETRIS!" he boldly wrote across the spires of St. Basil's cathedral.

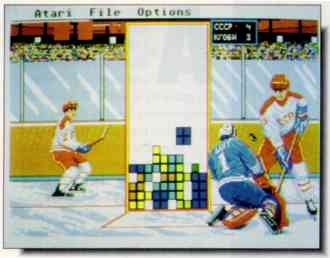

Tetris was a smash hit

in America.

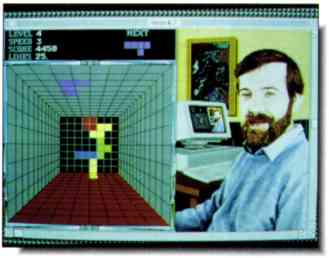

Welltris is a 3D version

of Tetris. Both Tetris and

Welltris were illustrated

with graphics inspired by

the photography book

A Day in the Life of the

Soviet Union.

Tetris Takes Off

People have been playing Tetris since 1985. "When Tetris became popular

it was like a fire in Moscow, Pazhitnov remembers. The first version of

the game was written for an old-technology DEC-compatible computer with

no graphics. Pazhitnov formed the game pieces, quartet of blocks, with

square bracket characters. The game play was simple: rotate the different

configurations of four blocks (Tetris is a play on the word tetra, which

is derived from the Greek tettares, meaning four) so that when they fall

to the bottom they form a solid line across the screen. The line disappears;

the blocks keep falling. You lose if the blocks stack up to the top of

the screen.

This deceptively simple task, the product of a mathematician's abstract, ordered mind, proved universally addictive. The game became a favorite pastime at the U.S.S.R. Academy of Sciences Computing Center (Academy Soft), where Pazhitnov still works as a programmer, designing CAD/CAM, speech recognition and psychology software. When a spruced-up version was ported to the IBM PC with the help of then-16-year-old hacker Vadim Gerasimov, Tetris spread throughout the East Bloc, leaping the Iron Curtain into Western Europe, where it was picked up for U.S. distribution by Spectrum Holobyte.

It was a spectacular hit in America - the first computer game from the Soviet Union - selling well over 100,000 copies and spawning versions for the Nintendo Gameboy and video arcades. It swept most of the 1988 Software Publishers Association Excellence in Software Awards for the entertainment category: Best Action/Strategy Program, Best Entertainment Program, Critic's Choice: Best Consumer Program and Best Original Game Achievement. And it's earned Pazhitnov enough money to make him well-off by Soviet standards.

Ironically, it's success was accidental. Tetris started life as an intellectual exercise.

"The best way to study new equipment is to write a small program," claims Pazhitnov, who speaks fairly fluent English. "I prefer to write games or puzzles."

Wanting only to see his little test program published, Pazhitnov assigned his rights to Academy Soft, whose director launched it westward. There was no other direction to go.

Softwhere?

The U.S.S.R.'s software market is virtually non-existent since the

country lacks an installed computer base to support it, says Pazhitnov,

who owns an IBM AT with an EGA board and what may be the only Nintendo

Gameboy system in Moscow.

"When I write a game I take in mind this (foreign) market, not the Soviet market," he says. He keeps up with developments overseas through the computer press (BYTE and PC World) and foreign businessmen. Even as he cocks one eye westward, Pazhitnov continues to write games that he likes to play. "Why do I have to write a hit each time?" he asks rhetorically, alluding to pressure to produce a smash follow-up to Tetris.

He refuses to cater to one segment of the foreign market: shoot'em up games. He doesn't like to play them and he doesn't want to program them. People who play his games, he brags, "have to think."

Pazhitnov is a prolific programmer, showing software houses about 10 games on this, his first, trip to America. He no longer gives away the rights to his work, having contracted with a joint venture company named Dialogue. He expects his third American release this summer, another geometric puzzle he calls Swap and Drop, but which Spectrum Holobyte wants to publish as Hatris.

Christmas release.

"It's another kind of thinking, another kind of playing," he says, trying

to differentiate number three from Tetris and its derivative, Welltris.

It's the end of a two-hour interview and clearly tired, Pazhitnov vaguely

describes his new game as requiring the player to swap and distribute two

different objects, matching them with others on the screen, then dropping

them. His candor dismays Spectrum's assistant marketing director, Rita

Harrington, who later shrugs off Pazhitnov's premature announcement of

a product for which the company has yet to develop packaging or promotion

as the price to pay for his politeness and business innocence.

| ATARI IN EASTERN EUROPE |

| The recent U.S. proposal to lift trade sanctions to Eastern Europe

was met with guarded enthusiasm by Atari Corp. The proposal was made to

COCOM, a 15-nation group that regulates technological transfers to the

East Bloc. At press time, COCOM had not announced a decision.

Max Bambridge, an Atari spokesperson, said the company's position on lifting trade sanctions is that "the free availability of computing power is not to our disadvantage." Bambridge acknowledged that due to the East Bloc's lack of consumer goods, like personal computers, "we have to plan to have long-term relationships where we can go in and provide support services, if needed, and sell upgrades." Atari will most likely pick East Germany to begin its marketing push, building on the company's current success in West Germany. "They (East Germany) may have the most viable of the economies in Eastern Europe right now," Bambridge said, "I would be extremely surprised if they did not turn out to be a major player very quickly." (Editor's Note: Although no official East German branch exists, Atari

reportedly commands between 30 and 50 percent of the 16-bit computer market

there, due to the STs availability in hard-currency stores. Atari presently

manufactures 8-bit machines in co-venture with the Soviet Union.)

|

Learning the Business

Pazhitnov is quickly losing that innocence. He learned a lot during

the Tetris negotiations, he says. The U.S.S.R. lacks the army of lawyers,

financiers and managers available to U.S. dealmakers, so Pazhitnov, the

point man of the Soviet software revolution, has fought alone to master

the unfamiliar contracts and agreements vital to his new business. Paperwork

isn't his favorite thing, he admits, but he accepts its necessity calmly;

like interviews, it's now part of his job.

Pazhitnov readily slips between jobs, from shy scientist to businessman. Upon meeting someone he whips out an embossed business card like any power-suited M.B.A. His cards, however, reflect the global nature of his enterprise; one side is in English, the other in Russian.

That dual nature is what has caught the eye of American business-people, eager to equate Perestroika's restructuring with embracing capitalism. About 150 of them crowded into the "First U.S.-Soviet Personal Computer Seminar," held at San Francisco State University the day after Pazhitnov's press reception at the St. Francis. Conference organizers expected a third that number.

Pazhitnov, the accidental entrepreneur, sat on a panel during the conference, facing the news camera along with the expatriates, Soviets and Americans promoting new trade ties. He didn't speak much. Always the gentleman, he told the audience he was happy to be in the United States and how much he liked the country. He didn't mention that sales pitches and public relations appearances barely left him time to take a brief walk around San Francisco. Like any quick study, he told the audience what they wanted to hear. And the audience embraced him, the Soviet Union's one-man game invasion, harbinger of other Cossacks charging the trade barriers.